Max Streicher

this flesh . . .

All things are transmutable, we learn as children: anything can become

something else and every place can be somewhere else. Objects can be

animate: independent lives can be created in toys, images, and

abstractions. Mysterious presences, experiences of extraordinary scale,

transforming characters and demons -- these are the very content and

fibre of the dream and nightmare world, spectres that pursue us

throughout our lives. The imaginary life of the child, and the fears and

fantasies of the adult, are connected by a common capacity for physical

joy and the awareness of physical frailty.

In his development of the inflatable as kinetic and interactive

artwork, and in his other multimedia installations, Max Streicher has

created images of our greatest joys and our deepest terrors, the site

where the imaginary lives of children and adults meet. Drawing on

imagery from literature, mythology, and the Bible (Streicher studied

theology before going to art school) his work provokes strong

spontaneous, psychological reactions in people of all ages and

backgrounds -- reactions that run deep and reveal insights into the

socially constructed ego.

A dream was the source for an important early work by Streicher

entitled We Will Name This Place..., 1988 (fig. 1). In the

Winter's College gallery at York University in Toronto Streicher removed

a large section of ceiling tile to reveal the building's inner

structure. Through this opening he installed three pâpier-maché

gargoyles -- dogs that appear to be charging from the sky. The

figures are a hybrid of Streicher's childhood dog, George, and gargoyles

seen by the artist on the cathedral in Swäbisch Gmünd, Germany.

Gargoyles, in the Middle Ages, were put on the outside of buildings to

ward off ghosts and malicious spirits. Dogs may be associated with the

hunt or the fear of being hunted. The same icon can be a benevolent

sign, however -- a messenger, a pet, or a companion on a spiritual

journey. Streicher used the gallery's acoustic ceiling panels as a

metaphorical skin, standing for the separation between interior and

exterior, conscious and subconscious realities.

The title We Will Name This Place... is a quotation from the

Bible referring to the dedication of sites where miracles had taken

place. At such a site a rock would be anointed with oil and the place

would be named. For the most part, miracles today are confined to

the pages of supermarket tabloids. But what of the world of dreams and

spirits, of clairvoyance and prescience? None of us can detach

completely from a world that is dark and irrational -- those aspects of

our experience that don't quite square with our mechanical, physical

understanding of the cosmos. Cracks occasionally occur in this

structure, puncturing our logical explanations and our propensity for

ordering -- "our cosmology." Through these cracks we

catch glimpses and we experience moments of insight, clarity, physical

ecstasy, and existential terror, coming to us in drips and drops and

splashes and waves -- like dogs pouring forth from above.

Perhaps this interest on the part of the artist in the leaky parts of

reality is less an attempt to describe the faults in our cosmology than

it is an attempt to describe the sacred in contemporary life. What is

sacred to us, what motivates our lives may not be sublime images of

heaven and earth, God and humanity, but rather the simple prospect of

financial gain, a new purchase, or a promotion at work. In The Life

We Are Living, 1990 (figs. 2 & 3) Streicher created a work that

was based upon his observation of the demolition of a church and the

construction, in its place, of a luxury condominium. The church tower, a

historical landmark, was preserved and the condominium structure built

to incorporate it. He imagined the construction worker as a spiritual

worker, a latter-day Levite constructing a temple to "speculative

real estate," embodying the spiritual values of Toronto in the late

eighties and early nineties.1

It may be a holdover of nineteenth-century romanticism in

contemporary culture that artists are directed to identify with the

mental patient, the prophet, or priest -- calling for spiritual values

in a materialistic and instrumentalized world. Condemning pleasures of

all kinds as vices, the spiritual outsider (read here the artist)

distrusts the world of sensation, preferring instead texts and the

interpretation of signs. Coming out of a Master of Fine Arts programme,

Streicher had absorbed these values, in effect not much different from

the values of the seminary school he had earlier attended. Streicher's

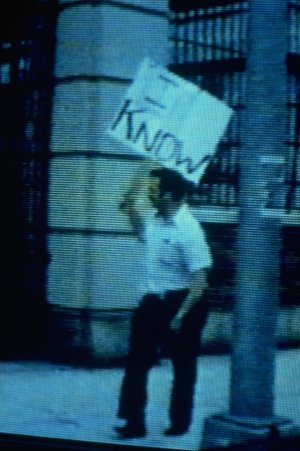

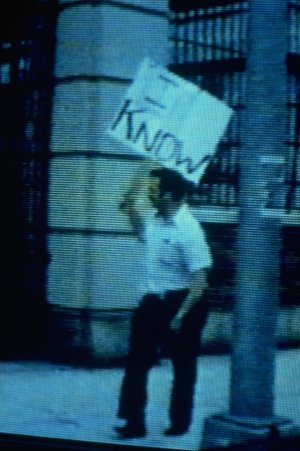

installation Panic and Fear, 1990 (fig. 4) is an ironic skewering

of such contemporary spiritual values. The installation, in a vacant

retail space in the Eaton Centre, Edmonton, consisted of a slide

projection of a mental patient carrying a sign that read, "I

know," and on the opposite wall a text: "Seeing now the

possibility of stilling forever our predisposition to panic and

fear."2 It is a bitter reflection and an outsider's

observation on the habit of pacifying existential anxiety through

shopping.

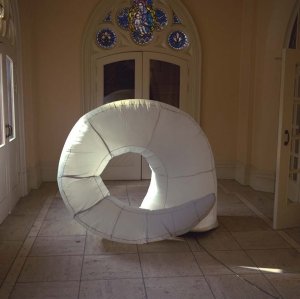

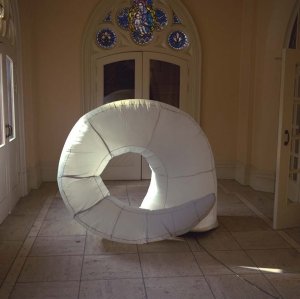

The first inflatable by Streicher was the work Breathe, 1989

(fig. 5) installed at the Bloor Street United Church. It was his first

work after graduate school, a piece he describes as whimsical, and at

the time not intended as a new direction or a sign of things to come. It

consisted of a sewn nylon bag, inflated by a vacuum cleaner. When fully

inflated, Breathe took the shape of a giant ram's horn. Each time

it inflated its motor and fan made a remarkably loud and high-pitched

sound and contrasted dramatically with the otherwise serene church

interior. There is something slightly rude about the piece: its size and

noise and its suggestion of a male erection.

Breathe made an impression on many people, including John Dickson and

Lyla Rye, who around that time found their own work tending to the

surrealistic and were looking around for like-minded artists to form an

artists' collective. They invited Streicher to exhibit with them and

other artists who later came to be known collectively as Nether Mind.3

Nether Mind's first exhibition took place in an old industrial basement

in the King Street West area of Toronto. Perhaps it was a combination of

factors: a collapsing economy (Streicher had just been laid off from his

day job at Bell Canada) and a dank, dark industrial basement as a venue

for this first show that generated the spirit that only a scarcity of

means and complete independence from institutional structures can

afford.

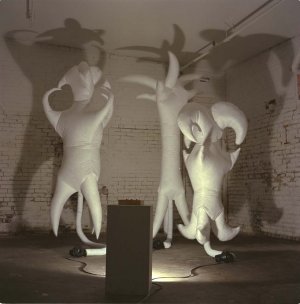

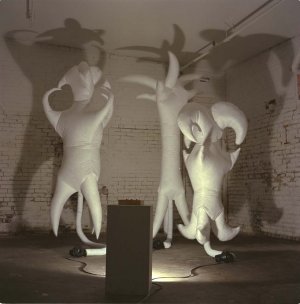

Streicher again returned to the inflatable for this group exhibition

and produced Boiler, 1991 (fig. 6). The figures in Boiler

were originally conceived as tripedal bunny suits-- each with three

ears, arms and legs tapered to points, like abstracted jesters. Viewers

animated the pieces by engaging switches that inflated them. The

inflation was startling, much like Breathe. The gloomy setting

only enhanced their ghostly presence. In the same exhibition, Streicher

exhibited Cellar. A blue sliding door in the same room as Boiler

opened to an even darker, danker space with water on the floor. Through

this door one could see limp, uninflated and very sad looking

"bunny suits" (the rejects of the Boiler research)

simply hung as though on meat hooks.4

The white, airy lightness and billowy softness of the Tyvek, the

synthetic, non-porous fabric that Streicher uses to make his inflatables,

inevitably recall clouds. In Where There Is Smoke, 1992 (fig. 7),

Streicher executed a private commission in the manner of a baroque

ceiling painter. The piece suggests the illusion of an opening through

the roof to the sky. It is a caricature of a cloud or of smoke, a

pulsating vision animated by the variable air currents of a rotating

valve mechanism.

Another play on this theme is Pillars of Cloud, 1992 (fig. 9).

The Pillars of Cloud were mounted on modified golf carts and

inflated by the squeezing of a hand break mechanism. The title is a

Biblical reference to when God was leading the Israelites out of Egypt

and he led them "by a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire

by night." In the process of realization, the soft billowy

cloud forms gradually came to resemble more the sharp "peaks of

church steeples and Thai architecture."5 These pillars of

cloud are like modern conveniences or consumer appliances -- personal

augers to the promised land -- and seem as though they should be

available at any department or hardware store.

In The Life We Are Living, Panic and Fear, and Pillars

of Cloud, Streicher suggests that the character of our individual

lives is in fact the acting out of our deepest spiritual beliefs in the

vernacular of mass consumption and entertainment. As such, the promise

of salvation and the spectre of perdition guide us in every consumer

selection and choice of diversion. This theme is also unmistakable in

the work this flesh..., 1993 (fig. 10), exhibited in a solo

exhibition at Galerie Articule in Montreal. this flesh... featured a

16-mm film loop of an appropriated inflatable -- an effigy crudely

painted to resemble the Toronto discount retailer Honest Ed with two

sewn-on arms spread wide to welcome (or bless?) shoppers. The image was

projected on an arrangement of four mirrors that fragmented the image as

well as enhancing the cruciform character of the inflatable. An LED

scrolled a text from Tertullian, from the treatise On the Flesh of

Christ: "(I mean) ... this flesh ... suffused with blood ...

built up with bones ... interwoven with nerves ... entwined with veins

... as born of a human ... and knows how to die ... undoubtedly human

... (I mean) ... this flesh ..."6

The cruciform resemblance of the Honest Ed effigy may be merely

coincidental, but the Christ-like death and resurrection character of

many of Streicher's figurative inflatables is hard to miss. These

figures, even at their most abstract, remind us of physical life as both

miraculous and ephemeral. In the same exhibition at Galerie Articule,

Streicher installed in the office the ceiling-mounted inflatable My

Dear One (fig. 11). Recalling the earlier ceiling-mounted Where

There Is Smoke, My Dear One featured two large inflatable

arms, angelically hovering and embracing the office workers. Its

message, that of a Walmart greeter or of Honest Ed himself -- one of

throbbing, all-embracing love.

In contrast to the cotton-candy sentiment of the inflatable, the

Galerie Articule exhibition also included a third piece demonstrating

Streicher's acidic side. Alchemist's Tongue: of which my rage is made

/ of which my fear is made, 1993 (fig. 12), was an installation of

approximately fifty tongues, some cast in sulphur and some in lye soap.

The tongues had been cast in flexible moulds and bound differently for

each casting so that every tongue was unique.7

As a piece of human anatomy, the tongue is perhaps second only to the

representation of the genitalia in its suggestiveness. It may be for its

unique sensitivity that modesty insists that the tongue remain private

and contained and shared only in the most intimate relationships.

Streicher views the tongue as a threshold organ between inner and outer,

a basic surface for the investigation of the world,and here, a literal

description of emotion in both form and substance.

The example of Joseph Beuys's sculpture and installations from the

1960s through the 1980s, as well as the work of other artists,

encouraged many to explore an alchemical relationship to their

materials. Contemporary sculptors may now use a broader range of

materials -- materials that in themselves may stand for feelings,

emotions, or abstractions. For Streicher, Alchemist's Tongue in

lye and sulphur, and later kaolin, is about inner transformation, like

the dogs in We Shall Name This Place breaking through the

ceiling. Illuminated by flashing lights, there is a Faustian character

to these glow-in-the dark tongues -- eloquent and impossible to resist,

yet bitter to the taste.

Three installations / interventions followed in 1994 that had fun

with the conventions of language, interpretation and political

postures.8 Streicher returned to the inflatable in 1995 with the

site-related piece Stalk (fig. 13) in a temporary exhibition

space in the Scotia Plaza concourse in Toronto's financial district.

Directly across from the exhibition was the men's clothier Moores, whose

promotions for various lines of clothing featured models in wilderness

and hunting scenes. The artist, interested in the culture of business

and how it is expressed by the language of the hunt, decided in turn to

produce his own homage. He fashioned four rifle-toting hunters in peaked

caps following their five bloodhounds. A rotating valve inflated and

deflated the figures by turns to mimic a slapstick chase. While the

human figure had often been implied in Streicher's inflatables, Stalk

gave the artist the opportunity to work out his first full

figurative work.

Stalk again situates the artist in the outsider position. The

physical and ideological lives of the financial district are seen from

the outside. The cartoon-like figures of Stalk can only be read as the

artist's comment on the absurdity of the maniacal hunt for gold. The

piece also allowed Streicher to find a figurative role for the

inflatable. The carnival figure, the caricature, the Macy's Thanksgiving

Day parade inflatables now became points of reference.

"Where my work does make reference to popular culture it is,

I feel, to such things as freak shows, carnival and the tradition of the

grotesque; expressions of 'low culture' that assert the body as

undetermined, disrupted, leaky and in direct confrontation to the

contained and controlled body represented by the dominant culture."9

If not of the exuberant body, Quartet in a Box, 1995 (fig. 17)

seems to communicate a body out of control, eliciting strong feelings of

fear and loathing. Four inflatable figures arranged in a circle, each

connected to an air source through the top of the head, pulse and writhe

in response to changing air pressure. It may be their horizontality or

the way they seem to jerk and quiver as they inflate, as if in some kind

of seizure, that inspires such feelings of revulsion and morbidity.

Sextet, 1996 (fig. 18) was an enlargement on the Quartet in

a Box model, but by subtle changes in articulation and the location

of the air source Streicher could achieve an entirely different effect.

In Sextet the figures are inflated through the navel area and they come

to life in a way that is even more dramatic than Quartet in a Box.

The inflation is coordinated so that each figure is in a different state

of inflation or deflation at any one time. This movement takes place

quickly and creates the impression of a certain type of childish play

energy -- manic, reckless, dizzying, out of control.10

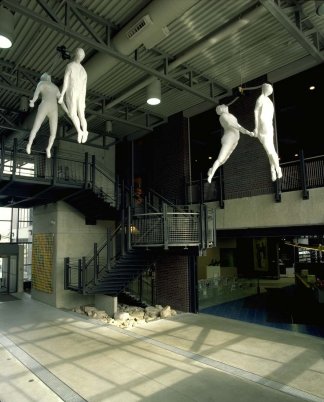

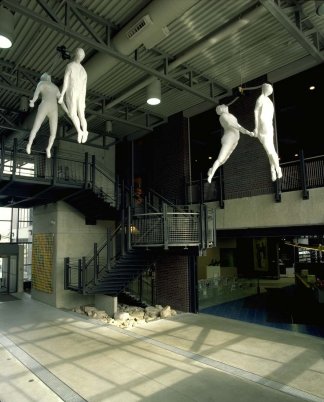

The occasion of the last Nether Mind exhibition in 1995 was the

stimulus for Balancing Act (fig. 18 & 19 opposite), one of

the artist's most elegant and eloquent pieces. Balancing Act

consists of two pair of figures suspended from the ceiling and inflated

by fans through rubber tubes in the area of the mouth.11 As a

figure quickly inflates, its chest fills and its arms thrust forward,

its back arches and legs and feet stiffen to a point. As it

deflates, the stiffness slowly disappears and the legs dangle down and

cross over. Streicher likens the effect to a dance, "as if dancers

had an exercise of having to make it appear as if all of the air were

draining from them."12

Indeed, there is a grace to the awakening and expiring acrobats, yet

within that grace there is also a startling and disturbing truth. When,

in the ballet Giselle, the tragic heroine dies after her dance

with the spirit of the woods, she gracefully succumbs to the stage

floor, her death the dance's denouement. The dancer acts as if dead and

the audience plays along, the saddest part being that she has finished

dancing. However, when the acrobat in Balancing Act loses air, it

is the illusion of physical life itself that disappears -- vanishes in

front of our eyes -- and becomes nothing more than a limp cloth bag.

Moreover, we have become intimate with these figures. As they inflate

and we hear the air rush into the body, we form a strange bond -- the

kind of feeling we experience with the breath of the other on our skin.

Yet, as Streicher is aware, "the source of that breath, industrial

fans and rather crudely fashioned valve mechanisms, are reminiscent of

respirators or some equally intrusive medical gadget, and this breath is

not life, just its sobering mechanics."13

Perhaps more than any other piece, Balancing Act makes us

focus on the central role of air and the imitation of breathing in

Streicher's inflatables. We relate to varying patterns of breathing, and

the action of air filling a body can suggest many things and elicit many

emotions. We breathe differently when asleep and awake, when we are

nervous, when we are calm. By adjusting and controlling the rhythm, the

sound and the speed of inflation and deflation, the artist manipulates

those perceptions and tells a story. Air, in the work of Max Streicher,

is indeed one of the substances of feeling.

The dragon exhibited with Balancing Act in the last Nether Mind

exhibition may have been an afterthought, in part because the warehouse

space for the exhibition was so vast. Streicher calls it a gift to the

show, "a prop, because Nether Mind shows were always more like

events or three-ring circuses."14 However, he had been

exploring the idea of scaling up his inflatables probably as early as

1993 when he appropriated the image of the Honest Ed inflatable in this

flesh.... The version of Boiler exhibited in the Naked State

exhibition in 1994 was a scaled-up version of the original to twice

lifesize. It was also around that time that the idea began for the

gigantic Swan Song (fig. 20), which he designed for the

exhibition Once Upon A Time at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery in

Lethbridge in 1996.15

In Swan Song Streicher was seeking "threatening beauty."16

He chose the swan because as an animal it is commonly known as a symbol

of beauty and elegance, but at the same time feared for its strength and

its potential for violence. Yard upon yard of silky white Tyvek in

softly undulating and pulsating forms created a dreamlike state for the

viewer to wade through. As in a dream, scale is distorted and no contour

is solid -- everything collapses to the touch or seems beyond reach.

"My intention is to overwhelm the gallery space and impose on

the viewer a sense of scale like that which a toddler might experience.

I am attempting to recreate a situation like that of childhood

encounters with humongous snow banks or haystacks; structures that

invite a physical exuberance which in turn leads the imagination .

. . In this work I want to physically embrace the viewer within a

tension between pleasure and threat, enchantment and self-reflexive

awareness."17

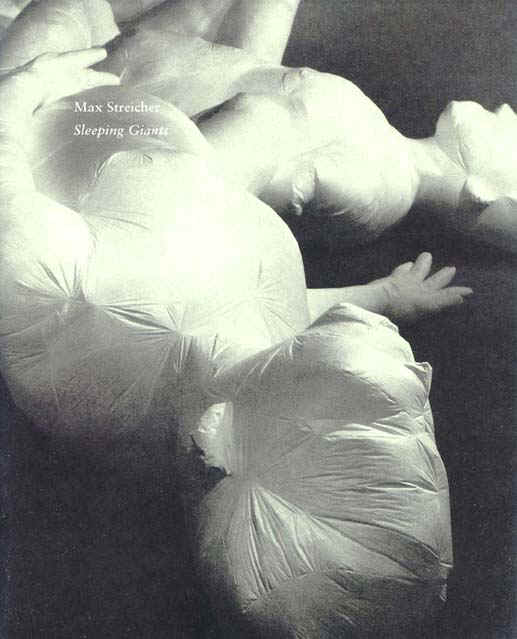

Sleeping Giants, 1998 (fig. 21, 22 & 23), exhibited at the

Cambridge Galleries, brought together the phenomenology of the physical

body first ventured in Quartet in a Box with the scale of Swan

Song. The giants in their great mass heaved and sighed to the timed

intervals of the fans. Lying on their backs and sides, heads rose from

the floor, legs stiffened, chests inflated, only to relax again, as if

in some futile attempt to get out of bed or off the couch. The giants

recalled the body as gross anatomy -- of a soul trapped within spoilable

flesh -- the dispirited body, incapable of action because of the

sentiment of futility. The giants also recalled the tragic body -- the

self perpetuating machine -- needy, voracious, desiring,

independent of consciousness and will.

The inflatable as art -- the balloon, the soap bubble, the inflatable

toy -- until now, has been dedicated to children. Max Streicher has

taken the inflatable, the prepubescent symbol of wonder and tragedy and

rehabilitated it, or rather, he has given it an adult life. He has done

this not by stripping the inflatable of those characteristics that

appeal to children, but by probing those aspects that are fundamental to

understanding ourselves. We favour children with balloons and they in

turn are fascinated by their lightness, enthralled by their buoyancy,

and devastated when they break. With each balloon, we create a round,

pudgy, brightly coloured life -- symbolizing at once our joy in creation

and our awareness of life's fragility. And therein lies its magic: the

inflatable makes the abstract character of our organic existence

visible. We know we were born from nothing, we feel our breath now, and

we know that we will expire.

Gordon Hatt

|

(fig. 1) We Will Name This

Place..., 1988, installation at Winter's College gallery, York

University. (Permanent installation at Fine Art Building, Phase II, York

University.) Photo: Max Streicher.

Fig. 3 Panic and Fear, 1990, slide

projection, text, installation, Eaton Centre, Edmonton, Alta., "The

Works" Festival.

Fig. 5 Breathe, 1989, "The

Crossing," Bloor St. United Church. Coordinated by Mediums Art

Centre, Toronto.

Fig. 6 Boiler, 1991, Tyvek, fans,

duct, and switches, 300 cm. high., Nether Mind collective exhibition,

1991.

Fig. 8 Where There Is Smoke, 1992,

installation. Collection of Marat Inc., Toronto.

Fig. 9 Pillars of Cloud, 1992,

Tyvek, modified golf carts, fans and switches, 351 cm high, Nether Mind

Collective exhibition.

Fig. 10 this flesh . . . ,

1993, 16 mm film loop, mirrors and LED sign, projection size: 190 x 190

cm, Galerie Articule, Montreal.

Fig. 11 My Dear One, Tyvek, fan,

flexible duct, lights, 10 m finger tip to finger tip, Galerie Articule,

1993.

Fig. 12 Alchemist's Tongue: of which

my rage is made/of which my fear is made, 1993, cast sulfur and lye

soap, flashing light bulbs. tongues: 8 to 45 cm high, Galerie Articule,

Montreal, May, 1993.

Fig. 13 Stalk, 1995, Site-specific

installation, Paul Petro Contemporary Art, Scotia Plaza, Toronto, 1995.

Fig. 17 Quartet in a Box, 1995,

Tyvek, electric blower, flexible duct cardboard box, 190 cm tall x 42 x

42 cm. , 00 Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Fig. 18 Sextet, 1996, each figure

250 cm high and Balancing Act, 1996 version, each figure 190 cm high,

installation at Synagoga na Palmovca, Prague, Czech Republic.

Photo: Daniel Sperl.

Fig. 19 Balancing Act, 1995,

Tyvek, electric blowers, flexible duct, 190 cm tall, Cambridge

Galleries, The Library & Gallery, Cambridge, 1998. Photo:

Robert McNair.

Fig. 20 Swan Song, 1996, Tyvek,

electric fans, switches 14' high, "Once Upon a Time," Southern

Alberta Art Gallery.

Fig. 21 Sleeping Giants,

1998, installation, at the Cambridge Galleries, the Library &

Gallery, Cambridge, Ontario, 1998.Photo:

Robert McNair.

Fig. 22 Sleeping Giants, 1998,

installation, at the Cambridge Galleries, the Library & Gallery,

Cambridge, Ontario, 1998.

Fig. 23 Sleeping Giants, 1998,

installation, at the Cambridge Galleries, the Library & Gallery,

Cambridge, Ontario, 1998. Photo:

Robert McNair.

|